সক্রেটিসের টিন্তার মূল কথা ছিল, "

মানুষের বুদ্ধিবৃত্তি দিয়ে প্রত্যেকটি বস্তুই যাচাই করে নিতে হবে। চিন্তার

ক্ষেত্রে অাবেগ বর্জন করতে হবে এবং বিবেক থেকে অনুমোদন না পেলে কেবল

কর্তৃপক্ষের হুকুম পালনের জন্য কোন কাজ সম্পাদন করা সৎ নাগরিকের উচিত

নয়। তথ্যগুলো যদিও অসম্পূর্ণ তবুও পাঠকদের জন্য রেখে দিলাম :

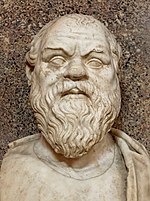

সক্রেটিস : সক্রেটিস (খ্রিস্টপূর্ব ৪৭০ - খ্রিস্টপূর্ব ৩৯৯) প্রাচীন গ্রিক দার্শনিক। এই মহান দার্শনিকের সম্পর্কে তথ্য লিখিতভাবে পাওয়া যায় কেবল মাত্র তাঁর শিষ্য প্লেটো-র ডায়ালগ এবং সৈনিক জেনোফন এর রচনা থেকে। তৎকালীন শাসকদের কোপানলে পড়ে তাঁকে হেমলক বিষ পানে মৃত্যুদন্ড দেয়া হয়। তাকে পশ্চিমা দর্শনের ভিত্তি স্থাপনকারী হিসেবে

চিহ্নিত করা হয়। তিনি এমন এক দার্শনিক চিন্তাধারা জন্ম দিয়েছেন যা দীর্ঘ ২০০০ বছর ধরে পশ্চিমা সংস্কৃতি, দর্শন ও সভ্যতাকে প্রবাবিত করেছে। সক্রেটিস ছিলেন এক মহান সাধারণ শিক্ষক, যিনি কেবল শিষ্য গ্রহণের মাধ্যমে শিক্ষা প্রদানে বিশ্বাসী ছিলেননা। তার কোন নির্দিষ্ট শিক্ষায়তন ছিলনা। যেখানেই যাকে পেতেন তাকেই মৌলিক প্রশ্নগুলোর উত্তর বোঝানোর চেষ্টা করতেন। তিনি মনব চেতনায় আমোদের ইচ্ছাকে নিন্দা করেছেন, কিন্তু সৌন্দর্য্য দ্বারা নিজেও আনন্দিত হয়েছেন।

প্লেটোর বর্ণনামতে সক্রেটিসের বাবার নাম সফ্রোনিস্কাস এবং মা'র নাম ফিনারিটি যিনি একজন ধাত্রী ছিলেন। তার স্ত্রীর নাম জানথিপি যার বয়স ছিল সক্রেটিসের থেকে অনেক কম। সংসার জীবনে তাদের তিন পুত্র সন্তানের জন্ম হয় যাদের নাম ছিল লামপ্রোক্লিস, সফ্রোনিস্কাস এবং মেনেজেনাস। সক্রেটিস তার শাস্তি কার্যকর হওয়ার পূর্বে পালিয়ে যাওয়ার অনুরোধ ফিরিয়ে দেন। এর পর নিজ পুত্রদের ত্যাগ করার জন্য সক্রেটিসের বন্ধু ক্রিটো তার সমালোচনা করেছিলেন। সক্রেটিসের জন্ম খ্রিস্টপূর্ব ৪৭০ অব্দে গ্রিসের এথেন্স নগরীতে এলোপাকি গোত্রে জন্মগ্রহণ করেছিলেন।

তিনি ঠিক কিভাবে জীবিকা নির্বাহ করতেন তা পরিষ্কার নয়। ফিলাসের টিমোন

এবং পরবর্তী আরও কিছু উৎসের অনুসারে প্রথম জীবনে তিনি তার বাবার পেশা

অবলম্বন করেছিলেন। তার বাবা ছিলেন একজন ভাস্কর। সে হিসেবে তার প্রথম জীবন

কেটেছে ভাস্করের কাজ করে। প্রাচীনকালে অনেকেই মনে করতো গ্রিসের

অ্যাক্রোপলিসে দ্বিতীয় শতাব্দী পর্যন্ত বিরাজমান ঈশ্বরের করুণা

চিহ্নিতকারী মূর্তিগুলো সক্রেটিসের হাতে তৈরী। অবশ্য বর্তমানকালের

বুদ্ধিজীবীরা এর সুনির্দিষ্ট প্রমাণ খুঁজে পাননি।[১]

অপরদিকে সক্রেটিস কোন পেশা অবলম্বন করেননি এমন প্রমাণও রয়েছে। জেনোফোন

রচিত সিম্পোজিয়ামে সক্রেটিসকে বলতে শোনা যায়, তিনি কখনও কোন পেশা অবলম্বন

করবেননা, কারণ তিনি ঠিক তা-ই করবেন যাকে সবচেয়ে গুরুত্বপূর্ণ বলে মনে

করেন আর তা হচ্ছে দর্শন সম্বন্ধে আলোচনা। এরিস্টোফেনিসের বর্ণনায় দেখা

যায় সক্রেটিস শিক্ষার বিনিময়ে অর্থ নিতেন এবং গ্রিসের চেরিফোনে একটি

সোফিস্ট বিদ্যালয়ও পরিচালনা করতেন। তার দ্য ক্লাউডস্ রচনায় এই ভাষ্য

পাওয়া গেছে। আবার প্লেটোর অ্যাপোলজি এবং জেনোফোনের সিম্পোজিয়ামে দেখা

যায় সক্রেটিস কখনই শিক্ষার বিনিময়ে অর্থ নেননি। বরঞ্চ তিনি তার দরিদ্রতার

দিকে নির্দেশ করেই প্রমাণ দিতেন যে, তিনি কোন পেশাদার শিক্ষক নন। তাকে

বলতে শোনা যায়:

সক্রেটিস দেখতে মোটেও সুদর্শন ছিলেননা। টাকবিশিষ্ট মাথা, চ্যাপ্টা অবনত নাক, ছোট ছোট চোখ, স্ফীত উদর এবং অস্বাভাবিক গতিভঙ্গির সমন্বয়ে গঠিত ছিল তার সামগ্রিক চেহারা। দেহের শ্রী তেমন না থাকলেও তার রসবোধ ছিল প্রখর। রঙ্গ করে প্রায়শই বলতেন: "নাসারন্ধ্রটি বড় হওয়ায় ঘ্রাণ নেয়ার বিশেষ সুবিধা হয়েছে; নাকটি বেশী চ্যাপ্টা হওয়াতে দৃষ্টি কোথাও বাঁধা পায়না।" কথাবার্তা ও আচার আচরণে তিনি ছিলেন মধুর ব্যক্তি। তাই যে-ই তার সাথে কথা বলতো সে-ই তার কথাবার্তা ও চরিত্রসৌন্দর্যে মুগ্ধ হয়ে যেতো। অধিকাংশের বর্ণনামতেই তিনি কোন শিক্ষা প্রতিষ্ঠানে শিক্ষা প্রদান করতেননা। রাস্তা-ঘাট, হাট-বাজারই ছিল তার শিক্ষায়তন। দর্শন অনুশীলন করতে যেয়ে সংসার ও জীবিকা সম্পর্কে খুবই উদাসীন হয়ে পড়েছিলেন। তিনি। এ কারণে শেষ জীবনে তার পুরো পরিবারকেই দারিদ্র ও অনাহারের মধ্যে জীবন যাপন করতে হয়। বেশিরভাগ সময়েই তিনি তার শিষ্যদের বাড়িতে পানাহার করতেন। স্ত্রী জানথিপির কাছে তিনি ছিলেন অবজ্ঞার পাত্র। জানথিপি প্রায়ই বলতেন, তার নিষ্কর্মা স্বামী পরিবারের জন্য সৌভাগ্য না এনে দুঃখ কষ্টই এনেছেন বেশি। তবে বাইরে বাইরে যতই তিক্ততা থাকুক অন্তরের অন্তস্থলে স্বামীর জন্য ভালোবাসা ছিল জানথিপির। সক্রেটিসের মৃত্যুতে তিনি যেভাবে শোক প্রকাশ করছেন তা থেকেই এই ভালোবাসার প্রমাণ পাওয়া যায়।[২]

এথেনীয় সরকার সক্রেটিসকে এমন দোষে দোষী বলে সাব্যস্ত করেছিল যাতে তার মৃত্যুদণ্ড প্রদান করা হতে পারে। কিন্তু তার গুণাবলী ও সত্যের প্রতি অটল মনোভাব সত্যিকার অর্থেই তৎকালীন সরকারি নীতি ও সমাজের সাথে সংঘর্ষ সৃষ্টিতে সমর্থ হয়েছিল। এ প্রসঙ্গে থুসিডাইডিস বলেছেন: "এক কথায় তার উদ্দেশ্য হাততালি দেয়া যেতে পারে যে প্রথবারের মত কোন একটি অনৈতিক আইন প্রণয়ন করেছে এবং যে অন্য এমন একজনকে কোন একটি অপরাধ করতে উৎসাহিত করে যে অপরাধের চিন্তা সে নিজ্ই কখনও করেনি।"[৩] সক্রেটিস সরাসরি বা অন্য কোন ভাবে বিভিন্ন সময়ে স্পার্টার অনেক নীতির প্রশংসা করেছে যে স্পার্টা ছিল এথেন্সের ঘোর শত্রু। এসব সত্ত্বেও ঐতিহাসিকভাবে সমাজের চোখে তার সবচেয়ে বড় অপরাধ ছিল সামাজিক ও নৈতিক ক্ষেত্রসমূহ নিয়ে তীব্র সমালোচনা। প্লেটোর মতে সক্রেটিস সরকারের জন্য একটি বিষফোঁড়ার কাজ করেছিলেন যার মূলে ছিল বিচার ব্যবস্থার প্রতিষ্ঠা ও ভালোর উদ্দেশ্য নিয়ে সমালোচনা। এথেনীয়দের সুবিচারের প্রতি নিষ্ঠা বাড়ানোর চেষ্টাকেই তার শাস্তির কারণ হিসেবে চিহ্নিত করা যেতে পারে।

প্লেটোর অ্যাপোলজি গ্রন্থের ভাষ্যমতে, সক্রেটিসের বন্ধু চেরিফোন একদিন ডেলফির ওরাক্লের কাছে যেয়ে প্রশ্নে করে যে, সক্রেটিসের চেয়ে প্রাজ্ঞ কেউ আছে কি-না। উত্তরে ওরাক্ল জানায় সক্রেটিসের চেয়ে প্রাজ্ঞ কেউ নেই। এর পর থেকেই সক্রেটিসকে সমাজের চোখে একজন রাষ্ট্রীয় অপরাধী ও সরকারের জন্য বিষফোঁড় হিসেবে দেখা হতে থাকে। সক্রেটিস বিশ্বাস করতেন ওরাক্লের কথাটি ছিল নিছক হেঁয়ালি। কারণ ওরাক্ল কখনও কোন নির্দিষ্ট ব্যক্তিকে জ্ঞান অর্জনের কারণে প্রশংসা করেনা। এটি আদৌ হেঁয়ালি ছিল কি-না তা পরীক্ষা করার জন্য সক্রেটিস সাধারণ এথেনীয়রা যে লোকদের জ্ঞানী বিবেচনা করতো তাদের কাছে গিয়ে কিছু প্রশ্ন করতে শুরু করেন। তিনি এথেন্সের মানুষদেরকে উত্তম, সৌন্দর্য্য এবং গুণ নিয়ে প্রশ্ন করেছিলেন। উত্তর শেনো তিনি বুঝতে পারেন এদের কেউই এই প্রশ্নগুলোর উত্তর জানে না কিন্তু মনে করে যে তারা সব জানে। এ থেকে তিনি সিদ্ধান্তে উপনীত হন এই দৃষ্টিভঙ্গিতে সক্রেটিস সবচেয়ে প্রাজ্ঞ ও জ্ঞানী যে, সে যা জানে না তা জানে বলে কখনও মনে করেনা। তার এ ধরনের হেঁয়ালিসূচক প্রজ্ঞা ও জ্ঞান তখনকার সনামধন্য এথেনীয়দের বিব্রত অবস্থার মধ্যে ফেলে দেয়। সক্রেটিসের সামনে গেলে তাদের মুখ শুকিয়ে যেতে শুরু করে। কারণ তারা কোন প্রশ্নের সদুত্তর দিতে পারতোনা। এ থেকেই সবাই তার বিরোধিতা শুরু করে।

এছাড়াও সক্রেটিসকে তরুণ সম্প্রদায়ের মধ্যে চরিত্রহীনতা ও দুর্নীতি প্রবেশ করানোর অভিযোগে অভিযুক্ত করা হয়। সব অভিযোগ বিবেচনায় এনে তাকে মৃত্যুদণ্ড প্রদান করা হয়। মৃত্যুর মাধ্যম নির্দিষ্ট হয় হেমলক বিষ পান। প্লেটোর ফিডো গ্রন্থের শেষে সক্রেটিসের মৃত্যুর পর্বের বর্ণনা উদ্ধৃত আছে। কারাগার থেকে পালানোর উদ্দেশ্যে সক্রেটিস turned down the pleas of Crito। বিষ পানের পর সক্রেটিসকে হাটতে আদেশ করা হয় যতক্ষণ না তার পদযুগল ভারী মনে হয়। শুয়ে পরার পর যে লোকটি সক্রেটিসের হাতে বিষ তুলে দিয়েছিল সে তার পায়ে পাতায় চিমটি কাটে। সক্রেটিস সে চিমটি অনুভব করতে পারেননি। তার দেহ বেয়ে অবশতা নেমে আসে। হৃদযন্ত্রের ক্রিয়া বন্ধ হয়ে যায়। মৃত্যুর পূর্বে তার বলা শেষ বাক্য ছিল: "ক্রিটো, অ্যাসক্লেপিয়াস আমাদের কাছে একটি মোরগ পায়, তার ঋণ পরিশোধ করতে ভুলো না যেন।" অ্যাসক্লেপিয়াস হচ্ছে গ্রিকদের আরোগ্য লাভের দেবতা। সক্রেটিসের শেষ কথা থেকে বোঝা যায়, তিনি বুঝাতে চেয়েছিলেন মৃত্যু হল আরোগ্য এবং দেহ থেকে আত্মার মুক্তি। রোমান দার্শনিক সেনেকা তার মৃত্যুর সময় সক্রেটিসের নকল করার চেষ্টা করেছিলেন। সেনেকাও সম্রাট নিরোর আদেশে আত্মহত্য করতে বাধ্য হয়েছিলেন।

Socrates' death is described at the end of Plato's Phaedo. Socrates turned down Crito's pleas to attempt an escape from prison. After drinking the poison, he was instructed to walk around until his legs felt numb. After he lay down, the man who administered the poison pinched his foot; Socrates could no longer feel his legs. The numbness slowly crept up his body until it reached his heart. Shortly before his death, Socrates speaks his last words to Crito: "Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don't forget to pay the debt."

Asclepius was the Greek god for curing illness, and it is likely Socrates' last words meant that death is the cure—and freedom, of the soul from the body. Additionally, in Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths, Robin Waterfield adds another interpretation of Socrates' last words. He suggests that Socrates was a voluntary scapegoat; his death was the purifying remedy for Athens' misfortunes. In this view, the token of appreciation for Asclepius would represent a cure for Athens' ailments.[52]

To illustrate the use of the Socratic method, a series of questions are posed to help a person or group to determine their underlying beliefs and the extent of their knowledge. The Socratic method is a negative method of hypothesis elimination, in that better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. It was designed to force one to examine one's own beliefs and the validity of such beliefs.

An alternative interpretation of the dialectic is that it is a method for direct perception of the Form of the Good. Philosopher Karl Popper describes the dialectic as "the art of intellectual intuition, of visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances."[61] In a similar vein, French philosopher Pierre Hadot suggests that the dialogues are a type of spiritual exercise. Hadot writes that "in Plato's view, every dialectical exercise, precisely because it is an exercise of pure thought, subject to the demands of the Logos, turns the soul away from the sensible world, and allows it to convert itself towards the Good."[62]

The matter is complicated because the historical Socrates seems to have been notorious for asking questions but not answering, claiming to lack wisdom concerning the subjects about which he questioned others.[64]

If anything in general can be said about the philosophical beliefs of Socrates, it is that he was morally, intellectually, and politically at odds with many of his fellow Athenians. When he is on trial for heresy and corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, he uses his method of elenchos to demonstrate to the jurors that their moral values are wrong-headed. He tells them they are concerned with their families, careers, and political responsibilities when they ought to be worried about the "welfare of their souls". Socrates' assertion that the gods had singled him out as a divine emissary seemed to provoke irritation, if not outright ridicule. Socrates also questioned the Sophistic doctrine that arete (virtue) can be taught. He liked to observe that successful fathers (such as the prominent military general Pericles) did not produce sons of their own quality. Socrates argued that moral excellence was more a matter of divine bequest than parental nurture. This belief may have contributed to his lack of anxiety about the future of his own sons.

Also, according to A. A. Long, "There should be no doubt that, despite his claim to know only that he knew nothing, Socrates had strong beliefs about the divine", and, citing Xenophon's Memorabilia, 1.4, 4.3,:

The one thing Socrates claimed to have knowledge of was "the art of love" (ta erôtikê). This assertion seems to be associated with the word erôtan, which means to ask questions. Therefore, Socrates is claiming to know about the art of love, insofar as he knows how to ask questions.[73][74]

The only time he actually claimed to be wise was within Apology, in which he says he is wise "in the limited sense of having human wisdom".[75] It is debatable whether Socrates believed humans (as opposed to gods like Apollo) could actually become wise. On the one hand, he drew a clear line between human ignorance and ideal knowledge; on the other, Plato's Symposium (Diotima's Speech) and Republic (Allegory of the Cave) describe a method for ascending to wisdom.

In Plato's Theaetetus (150a), Socrates compares his treatment of the young people who come to him for philosophical advice to the way midwives treat their patients, and the way matrimonial matchmakers act. He says that he himself is a true matchmaker (προμνηστικός promnestikós) in that he matches the young man to the best philosopher for his particular mind. However, he carefully distinguishes himself from a panderer (προᾰγωγός proagogos) or procurer. This distinction is echoed in Xenophon's Symposium (3.20), when Socrates jokes about his certainty of being able to make a fortune, if he chose to practice the art of pandering. For his part as a philosophical interlocutor, he leads his respondent to a clearer conception of wisdom, although he claims he is not himself a teacher (Apology). His role, he claims, is more properly to be understood as analogous to a midwife (μαῖα maia).[76][77]

In the Theaetetus, Socrates explains that he is himself barren of theories, but knows how to bring the theories of others to birth and determine whether they are worthy or mere "wind eggs" (ἀνεμιαῖον anemiaion). Perhaps significantly, he points out that midwives are barren due to age, and women who have never given birth are unable to become midwives; they would have no experience or knowledge of birth and would be unable to separate the worthy infants from those that should be left on the hillside to be exposed. To judge this, the midwife must have experience and knowledge of what she is judging.[78][79]

Socrates believed the best way for people to live was to focus on the

pursuit of virtue rather than the pursuit, for instance, of material

wealth.[80]

He always invited others to try to concentrate more on friendships and a

sense of true community, for Socrates felt this was the best way for

people to grow together as a populace.[81]

His actions lived up to this standard: in the end, Socrates accepted

his death sentence when most thought he would simply leave Athens, as he

felt he could not run away from or go against the will of his

community; as mentioned above, his reputation for valor on the

battlefield was without reproach.

The idea that there are certain virtues formed a common thread in Socrates' teachings. These virtues represented the most important qualities for a person to have, foremost of which were the philosophical or intellectual virtues. Socrates stressed that "the unexamined life is not worth living [and] ethical virtue is the only thing that matters."[82]

Socrates' opposition to democracy is often denied, and the question is one of the biggest philosophical debates when trying to determine exactly what Socrates believed. The strongest argument of those who claim Socrates did not actually believe in the idea of philosopher kings is that the view is expressed no earlier than Plato's Republic, which is widely considered one of Plato's "Middle" dialogues and not representative of the historical Socrates' views. Furthermore, according to Plato's Apology of Socrates, an "early" dialogue, Socrates refused to pursue conventional politics; he often stated he could not look into other's matters or tell people how to live their lives when he did not yet understand how to live his own. He believed he was a philosopher engaged in the pursuit of Truth, and did not claim to know it fully. Socrates' acceptance of his death sentence after his conviction can also be seen to support this view. It is often claimed much of the anti-democratic leanings are from Plato, who was never able to overcome his disgust at what was done to his teacher. In any case, it is clear Socrates thought the rule of the Thirty Tyrants was also objectionable; when called before them to assist in the arrest of a fellow Athenian, Socrates refused and narrowly escaped death before the Tyrants were overthrown. He did, however, fulfill his duty to serve as Prytanis when a trial of a group of Generals who presided over a disastrous naval campaign were judged; even then, he maintained an uncompromising attitude, being one of those who refused to proceed in a manner not supported by the laws, despite intense pressure.[84] Judging by his actions, he considered the rule of the Thirty Tyrants less legitimate than the Democratic Senate that sentenced him to death.

Socrates' apparent respect for democracy is one of the themes emphasized in the 2008 play Socrates on Trial by Andrew David Irvine. Irvine argues that it was because of his loyalty to Athenian democracy that Socrates was willing to accept the verdict of his fellow citizens. As Irvine puts it, "During a time of war and great social and intellectual upheaval, Socrates felt compelled to express his views openly, regardless of the consequences. As a result, he is remembered today, not only for his sharp wit and high ethical standards, but also for his loyalty to the view that in a democracy the best way for a man to serve himself, his friends, and his city—even during times of war—is by being loyal to, and by speaking publicly about, the truth."[85]

Hemlock: Conium maculatum (hemlock or poison hemlock) is a highly poisonous perennial herbaceous flowering plant in the carrot family Apiaceae, native to Europe and North Africa.[2]

Conium comes from the Greek konas (meaning to whirl), in reference to vertigo, one of the symptoms of ingesting the plant.[6]

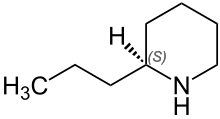

Eight piperidinic alkaloids have been identified in C. maculatum. Two of them, gamma-coniceine and coniine,

are generally the most abundant, and they account for most of the

plant's acute and chronic toxicity. These alkaloids are synthesized by

the plant from four acetate units from the metabolic pool, forming a

polyketoacid which cyclises through an aminotransferase and forms

gamma-coniceine as the parent alkaloid via reduction by a NADPH-dependent reductase.

Conium contains the piperidine alkaloids coniine, N-methylconiine, conhydrine, pseudoconhydrine, and gamma-coniceine (or g-coniceïne), which is the precursor of the other hemlock alkaloids.[7][11][12]

Coniine has a chemical structure and pharmacological properties similar to nicotine,[7][13] and disrupts the workings of the central nervous system through action on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. In high enough concentrations, coniine can be dangerous to humans and livestock.[12] Due to high potency, the ingestion of seemingly small doses can easily result in respiratory collapse and death.[14] Coniine causes death by blocking the neuromuscular junction in a manner similar to curare; this results in an ascending muscular paralysis with eventual paralysis of the respiratory muscles which results in death due to lack of oxygen to the heart and brain. Death can be prevented by artificial ventilation until the effects have worn off 48–72 hours later.[7] For an adult, the ingestion of more than 100 mg (0.1 gram) of coniine (about six to eight fresh leaves, or a smaller dose of the seeds or root) may be fatal.[15]

It has been observed that poisoned animals tend to return to feed on this plant. Chronic toxicity affects only pregnant animals. When they are poisoned by C. maculatum during the fetus' organ formation period, the offspring is born with malformations, mainly palatoschisis and multiple congenital contractures (MCC; frequently described as arthrogryposis). Chronic toxicity is irreversible and although MCC can be surgically corrected in some cases, most of the malformed animals are lost. Such losses may be underestimated, at least in some regions, because of the difficulty in associating malformations with the much earlier maternal poisoning.

Since no specific antidote is available, prevention is the only way to deal with the production losses caused by the plant. Control with herbicides and grazing with less susceptible animals (such as sheep) have been suggested. C. maculatum alkaloids can enter the human food chain via milk and fowl.[24]

সক্রেটিস : সক্রেটিস (খ্রিস্টপূর্ব ৪৭০ - খ্রিস্টপূর্ব ৩৯৯) প্রাচীন গ্রিক দার্শনিক। এই মহান দার্শনিকের সম্পর্কে তথ্য লিখিতভাবে পাওয়া যায় কেবল মাত্র তাঁর শিষ্য প্লেটো-র ডায়ালগ এবং সৈনিক জেনোফন এর রচনা থেকে। তৎকালীন শাসকদের কোপানলে পড়ে তাঁকে হেমলক বিষ পানে মৃত্যুদন্ড দেয়া হয়। তাকে পশ্চিমা দর্শনের ভিত্তি স্থাপনকারী হিসেবে

চিহ্নিত করা হয়। তিনি এমন এক দার্শনিক চিন্তাধারা জন্ম দিয়েছেন যা দীর্ঘ ২০০০ বছর ধরে পশ্চিমা সংস্কৃতি, দর্শন ও সভ্যতাকে প্রবাবিত করেছে। সক্রেটিস ছিলেন এক মহান সাধারণ শিক্ষক, যিনি কেবল শিষ্য গ্রহণের মাধ্যমে শিক্ষা প্রদানে বিশ্বাসী ছিলেননা। তার কোন নির্দিষ্ট শিক্ষায়তন ছিলনা। যেখানেই যাকে পেতেন তাকেই মৌলিক প্রশ্নগুলোর উত্তর বোঝানোর চেষ্টা করতেন। তিনি মনব চেতনায় আমোদের ইচ্ছাকে নিন্দা করেছেন, কিন্তু সৌন্দর্য্য দ্বারা নিজেও আনন্দিত হয়েছেন।

জীবনী

জীবন ও কর্ম

সক্রেটিসের জীবনের বিস্তৃত সূত্র হিসেবে বর্তমানকালে তিনটি উৎসের উল্লেখ করা যেতে পারে: প্লেটোর ডায়ালগসমূহ, এরিস্টোফেনিসের নাটকসমূহ এবং জেনোফেনোর ডায়ালগসমূহ। সক্রেটিস নিজে কিছু লিখেছেন বলে কোন প্রমাণ পাওয়া যায়নি। এরিস্টোফেনিসের নাটক দ্য ক্লাউডে সক্রেটিসকে দেখানো হয়েছে একজন ভাঁড় হিসেবে যে তার ছাত্রদের শিক্ষা দেয় কিভাবে ঋণের দায় থেকে বুদ্ধি খাটিয়ে মুক্তি পাওয়া যায়। এরিস্টোফেনিসের অধিকাংশ রচনাই যেহেতু ব্যাঙ্গাত্মক ছিল সেহেতু এই রচনায় সক্রেটিসকে যেভাবে ফুটিয়ে তোলা হয়েছে তা সম্পূর্ণরুপে গ্রহণযোগ্য নয়।প্লেটোর বর্ণনামতে সক্রেটিসের বাবার নাম সফ্রোনিস্কাস এবং মা'র নাম ফিনারিটি যিনি একজন ধাত্রী ছিলেন। তার স্ত্রীর নাম জানথিপি যার বয়স ছিল সক্রেটিসের থেকে অনেক কম। সংসার জীবনে তাদের তিন পুত্র সন্তানের জন্ম হয় যাদের নাম ছিল লামপ্রোক্লিস, সফ্রোনিস্কাস এবং মেনেজেনাস। সক্রেটিস তার শাস্তি কার্যকর হওয়ার পূর্বে পালিয়ে যাওয়ার অনুরোধ ফিরিয়ে দেন। এর পর নিজ পুত্রদের ত্যাগ করার জন্য সক্রেটিসের বন্ধু ক্রিটো তার সমালোচনা করেছিলেন। সক্রেটিসের জন্ম খ্রিস্টপূর্ব ৪৭০ অব্দে গ্রিসের এথেন্স নগরীতে এলোপাকি গোত্রে জন্মগ্রহণ করেছিলেন।

ইন্দ্রিয়গত আমোদের কবল থেকে আলসিবিয়াডিসকে ছাড়িয়ে নিয়ে যাচ্ছেন সক্রেটিস। ১৭৯১ সালে জ্যাঁ-ব্যাপ্টিস্ট রেনোঁ কর্তৃক অঙ্কিত চিত্র।

নিজেকে অন্যের মধ্যে বিলিয়ে দেয়াই আমার অভ্যাস; আর এজন্যই এমনিতে না পেলে পয়সাকড়ি দিয়েও আমি দার্শনিক আলোচনার সাথী সংগ্রহ করতাম।প্লেটোর ডায়ালগগুলোর বিভিন্ন স্থানে লেখা হয়েছে যে সক্রেটিস কোন এক সময় সামরিক বাহিনীতে যোগ দিয়েছিলেন। প্লেটোর বর্ণনায় সক্রেটিস বলেন, তিনি তিন তিনটি অভিযানে এথেনীয় সেনাবাহিনীর সাথে যোগ দিয়েছেন। এই অভিযানগুলো সংঘটিত হয়েছিল যখাক্রমে পটিডিয়া, অ্যাম্ফিপোলিস এবং ডেলিয়ামে। সিম্পোজিয়ামে আলসিবিয়াডিস নামক চরিত্র বর্ণনা করে পটিডিয়া এবং ডেলিয়ামের যুদ্ধে সক্রেটিসের বীরত্বের কথা এবং এর আগের যুদ্ধে তিনি কিভাবে নিজের প্রাণ বাঁচিয়েছিলেন সেকথা। ডেলিয়ামের যুদ্ধে তার অসাধারণ অবদানের কথা লাকিস নামক রচনাতেও বর্ণীত হয়েছে। মাঝেমধ্যেই সক্রেটিস বিচারালয়ের সমস্যাকে যুদ্ধক্ষেত্রের সাথে তুলনা করেছেন। তিনি বলেন একজন বিচারক দর্শন থেকে সরে আসবেন কি-না তা ভেবে দেখা তেমনই প্রয়োজন যেমন উপযুক্ত পরিস্থিতি সৃষ্টি হলে যুদ্ধক্ষেত্র ত্যাগ করবে কি-না তা একজন সৈন্যের ভেবে দেখা প্রয়োজন।

সক্রেটিস দেখতে মোটেও সুদর্শন ছিলেননা। টাকবিশিষ্ট মাথা, চ্যাপ্টা অবনত নাক, ছোট ছোট চোখ, স্ফীত উদর এবং অস্বাভাবিক গতিভঙ্গির সমন্বয়ে গঠিত ছিল তার সামগ্রিক চেহারা। দেহের শ্রী তেমন না থাকলেও তার রসবোধ ছিল প্রখর। রঙ্গ করে প্রায়শই বলতেন: "নাসারন্ধ্রটি বড় হওয়ায় ঘ্রাণ নেয়ার বিশেষ সুবিধা হয়েছে; নাকটি বেশী চ্যাপ্টা হওয়াতে দৃষ্টি কোথাও বাঁধা পায়না।" কথাবার্তা ও আচার আচরণে তিনি ছিলেন মধুর ব্যক্তি। তাই যে-ই তার সাথে কথা বলতো সে-ই তার কথাবার্তা ও চরিত্রসৌন্দর্যে মুগ্ধ হয়ে যেতো। অধিকাংশের বর্ণনামতেই তিনি কোন শিক্ষা প্রতিষ্ঠানে শিক্ষা প্রদান করতেননা। রাস্তা-ঘাট, হাট-বাজারই ছিল তার শিক্ষায়তন। দর্শন অনুশীলন করতে যেয়ে সংসার ও জীবিকা সম্পর্কে খুবই উদাসীন হয়ে পড়েছিলেন। তিনি। এ কারণে শেষ জীবনে তার পুরো পরিবারকেই দারিদ্র ও অনাহারের মধ্যে জীবন যাপন করতে হয়। বেশিরভাগ সময়েই তিনি তার শিষ্যদের বাড়িতে পানাহার করতেন। স্ত্রী জানথিপির কাছে তিনি ছিলেন অবজ্ঞার পাত্র। জানথিপি প্রায়ই বলতেন, তার নিষ্কর্মা স্বামী পরিবারের জন্য সৌভাগ্য না এনে দুঃখ কষ্টই এনেছেন বেশি। তবে বাইরে বাইরে যতই তিক্ততা থাকুক অন্তরের অন্তস্থলে স্বামীর জন্য ভালোবাসা ছিল জানথিপির। সক্রেটিসের মৃত্যুতে তিনি যেভাবে শোক প্রকাশ করছেন তা থেকেই এই ভালোবাসার প্রমাণ পাওয়া যায়।[২]

বিচার ও মৃত্যু

দ্য ডেথ অফ সক্রেটিস, ১৭৮৭ সালে জ্যাক লুই ডেভিড কর্তৃক অঙ্কিত চিত্র

মূল নিবন্ধ: সক্রেটিসের বিচার

এথেনীয় সাম্রাজ্যের সর্বোচ্চ ক্ষমতার যুগ থেকে পেলোপনেশীয় যুদ্ধে

স্পার্টা ও তার মিত্রবাহিনীর কাছে হেরে যাওয়া পর্যন্ত পুরো সময়টাই

সক্রেটিস বেঁচে ছিলেন। পরাজয়ের গ্লানি ভুলে এথেন্স যখন পুনরায় স্থিত

হওয়ার চেষ্টা করছিল তখনই সেখানকার জনগণ একটি কর্মক্ষম সরকার পদ্ধতি হিসেকে

গণতন্ত্রের সঠিকত্ব নিয়ে প্রশ্ন তোলা শুরু করেছিল। সক্রেটিসও গণতন্ত্রের

একজন সমালোচক হিসেবে আত্মপ্রকাশ করেন। তাই অনেকে সক্রেটিসের বিচার ও

মৃত্যুটিকে রাজনৈতিক উদ্দেশ্যপ্রণোদিত বলে ব্যাখ্যা করেছেন।এথেনীয় সরকার সক্রেটিসকে এমন দোষে দোষী বলে সাব্যস্ত করেছিল যাতে তার মৃত্যুদণ্ড প্রদান করা হতে পারে। কিন্তু তার গুণাবলী ও সত্যের প্রতি অটল মনোভাব সত্যিকার অর্থেই তৎকালীন সরকারি নীতি ও সমাজের সাথে সংঘর্ষ সৃষ্টিতে সমর্থ হয়েছিল। এ প্রসঙ্গে থুসিডাইডিস বলেছেন: "এক কথায় তার উদ্দেশ্য হাততালি দেয়া যেতে পারে যে প্রথবারের মত কোন একটি অনৈতিক আইন প্রণয়ন করেছে এবং যে অন্য এমন একজনকে কোন একটি অপরাধ করতে উৎসাহিত করে যে অপরাধের চিন্তা সে নিজ্ই কখনও করেনি।"[৩] সক্রেটিস সরাসরি বা অন্য কোন ভাবে বিভিন্ন সময়ে স্পার্টার অনেক নীতির প্রশংসা করেছে যে স্পার্টা ছিল এথেন্সের ঘোর শত্রু। এসব সত্ত্বেও ঐতিহাসিকভাবে সমাজের চোখে তার সবচেয়ে বড় অপরাধ ছিল সামাজিক ও নৈতিক ক্ষেত্রসমূহ নিয়ে তীব্র সমালোচনা। প্লেটোর মতে সক্রেটিস সরকারের জন্য একটি বিষফোঁড়ার কাজ করেছিলেন যার মূলে ছিল বিচার ব্যবস্থার প্রতিষ্ঠা ও ভালোর উদ্দেশ্য নিয়ে সমালোচনা। এথেনীয়দের সুবিচারের প্রতি নিষ্ঠা বাড়ানোর চেষ্টাকেই তার শাস্তির কারণ হিসেবে চিহ্নিত করা যেতে পারে।

প্লেটোর অ্যাপোলজি গ্রন্থের ভাষ্যমতে, সক্রেটিসের বন্ধু চেরিফোন একদিন ডেলফির ওরাক্লের কাছে যেয়ে প্রশ্নে করে যে, সক্রেটিসের চেয়ে প্রাজ্ঞ কেউ আছে কি-না। উত্তরে ওরাক্ল জানায় সক্রেটিসের চেয়ে প্রাজ্ঞ কেউ নেই। এর পর থেকেই সক্রেটিসকে সমাজের চোখে একজন রাষ্ট্রীয় অপরাধী ও সরকারের জন্য বিষফোঁড় হিসেবে দেখা হতে থাকে। সক্রেটিস বিশ্বাস করতেন ওরাক্লের কথাটি ছিল নিছক হেঁয়ালি। কারণ ওরাক্ল কখনও কোন নির্দিষ্ট ব্যক্তিকে জ্ঞান অর্জনের কারণে প্রশংসা করেনা। এটি আদৌ হেঁয়ালি ছিল কি-না তা পরীক্ষা করার জন্য সক্রেটিস সাধারণ এথেনীয়রা যে লোকদের জ্ঞানী বিবেচনা করতো তাদের কাছে গিয়ে কিছু প্রশ্ন করতে শুরু করেন। তিনি এথেন্সের মানুষদেরকে উত্তম, সৌন্দর্য্য এবং গুণ নিয়ে প্রশ্ন করেছিলেন। উত্তর শেনো তিনি বুঝতে পারেন এদের কেউই এই প্রশ্নগুলোর উত্তর জানে না কিন্তু মনে করে যে তারা সব জানে। এ থেকে তিনি সিদ্ধান্তে উপনীত হন এই দৃষ্টিভঙ্গিতে সক্রেটিস সবচেয়ে প্রাজ্ঞ ও জ্ঞানী যে, সে যা জানে না তা জানে বলে কখনও মনে করেনা। তার এ ধরনের হেঁয়ালিসূচক প্রজ্ঞা ও জ্ঞান তখনকার সনামধন্য এথেনীয়দের বিব্রত অবস্থার মধ্যে ফেলে দেয়। সক্রেটিসের সামনে গেলে তাদের মুখ শুকিয়ে যেতে শুরু করে। কারণ তারা কোন প্রশ্নের সদুত্তর দিতে পারতোনা। এ থেকেই সবাই তার বিরোধিতা শুরু করে।

এছাড়াও সক্রেটিসকে তরুণ সম্প্রদায়ের মধ্যে চরিত্রহীনতা ও দুর্নীতি প্রবেশ করানোর অভিযোগে অভিযুক্ত করা হয়। সব অভিযোগ বিবেচনায় এনে তাকে মৃত্যুদণ্ড প্রদান করা হয়। মৃত্যুর মাধ্যম নির্দিষ্ট হয় হেমলক বিষ পান। প্লেটোর ফিডো গ্রন্থের শেষে সক্রেটিসের মৃত্যুর পর্বের বর্ণনা উদ্ধৃত আছে। কারাগার থেকে পালানোর উদ্দেশ্যে সক্রেটিস turned down the pleas of Crito। বিষ পানের পর সক্রেটিসকে হাটতে আদেশ করা হয় যতক্ষণ না তার পদযুগল ভারী মনে হয়। শুয়ে পরার পর যে লোকটি সক্রেটিসের হাতে বিষ তুলে দিয়েছিল সে তার পায়ে পাতায় চিমটি কাটে। সক্রেটিস সে চিমটি অনুভব করতে পারেননি। তার দেহ বেয়ে অবশতা নেমে আসে। হৃদযন্ত্রের ক্রিয়া বন্ধ হয়ে যায়। মৃত্যুর পূর্বে তার বলা শেষ বাক্য ছিল: "ক্রিটো, অ্যাসক্লেপিয়াস আমাদের কাছে একটি মোরগ পায়, তার ঋণ পরিশোধ করতে ভুলো না যেন।" অ্যাসক্লেপিয়াস হচ্ছে গ্রিকদের আরোগ্য লাভের দেবতা। সক্রেটিসের শেষ কথা থেকে বোঝা যায়, তিনি বুঝাতে চেয়েছিলেন মৃত্যু হল আরোগ্য এবং দেহ থেকে আত্মার মুক্তি। রোমান দার্শনিক সেনেকা তার মৃত্যুর সময় সক্রেটিসের নকল করার চেষ্টা করেছিলেন। সেনেকাও সম্রাট নিরোর আদেশে আত্মহত্য করতে বাধ্য হয়েছিলেন।

দার্শনিক পদ্ধতি

মূল নিবন্ধ: সক্রেটিসের পদ্ধতি

সক্রেটিস দার্শনিক জেনোর

মত দ্বান্দ্বিক পদ্ধতিতে বিশ্বাসী ছিলেন। এই পদ্ধতিতে প্রথমে প্রতিপক্ষের

মত স্বীকার করে নেয়া হয়, কিন্তু এর পর যুক্তির মাধ্যমে সেই মতকে খণ্ডন

করা হয়। এই পদ্ধতির একটি প্রধান বাহন হল প্রশ্ন-উত্তর। সক্রেটিস

প্রশ্নোত্তরের মাধ্যমেই দার্শনিক আলোচনা চালিয়ে যেতেন। প্রথমে প্রতিপক্ষের

জন্য যুক্তির ফাঁদ পাততেন এবং একের পর এক প্রশ্ন করতে থাকতেন। যতক্ষণ না

প্রতিপক্ষ পরাজিত হয়ে নিজের ভুল স্বীকার করে নেয় ততক্ষণ প্রশ্ন চলতেই

থাকতো। সক্রেটিসের এই পদ্ধতির অপর নাম সক্রেটিসের শ্লেষ (Socratic irony)।দার্শনিক চিন্তাধারা

জ্ঞানতত্ত্ব ও জ্ঞানানুরাগ

সদ্গুণ

রাজনীতি

মরমীবাদ

কিছু দার্শনিক উক্তি

- অপরিক্ষীত জীবন নিয়ে বেঁচে থাকা গ্লানিকর।

- পোষাক হলো বাইরের আবরণ, মানুষের আসল সৌন্দর্য হচ্ছে তার জ্ঞান।

- নিজেকে জান।

- টাকা বিনিময়ে শিক্ষা অর্জনের চেয়ে অশিক্ষিত থাকা ভাল।

- জ্ঞানের শিক্ষকের কাজ হচ্ছে কোনো ব্যক্তিকে প্রশ্ন করে তার কাছ থেকে উত্তর জেনে দেখানো যে জ্ঞানটা তার মধহ্যেই ছিল।

- তারা জানে না যে তারা জানে না, আমি জানি যে আমি কিছু জানি না।

- নারী জগতে বিশৃঙ্খলা ও ভাঙ্গনের সর্বশ্রেষ্ঠ উৎস। সে দাফালি বৃক্ষের

ন্যায় যাহা বাহ্যত খুব সুন্দর দেখায়। কিন্তু চড়ুই পাখি ইহা ভক্ষণ করিলে

ইহাদের মৃত্যু অনিবার্য।

- পৃথিবীতে শুধুমাত্র একটি-ই ভাল আছে, জ্ঞান। আর একটি-ই খারাপ আছে, অজ্ঞতা।

- আমি কাউকে কিছু শিক্ষা দিতে পারব না, আমি শুধু তাদের চিন্তা করাতে পারব।

- বিস্ময় হল জ্ঞানের শুরু।

- টাকার বিনিময়ে শিক্ষা অর্জনের চেয়ে অশিক্ষিত থাকা ভাল।

- জ্ঞানের শিক্ষকের কাজ হচ্ছে কোনো ব্যক্তিকে প্রশ্ন করে তার কাছ থেকে উত্তর জেনে দেখানো যে জ্ঞানটা তার মধ্যেই ছিল।

- বন্ধু হচ্ছে দুটি হৃদয়ের একটি অভিন্ন মন।

- অপরীক্ষিত জীবন নিয়ে বেঁচে থাকা গ্লানিকর।

- পোশাক হলো বাইরের আবরণ, মানুষের আসল সৌন্দর্য হচ্ছে তার জ্ঞান।

- নিজেকে জান।

- প্রকৃত জ্ঞান নিজেকে জানার মধ্যে, অন্য কিছু জানার মধ্যে নয়।

- তুমি কিছুই জান না এটা জানা-ই জ্ঞানের আসল মানে।

- যাই হোক বিয়ে কর। তোমার স্ত্রী ভাল হলে তুমি হবে সুখী, আর খারাপ হলে হবে দার্শনিক।

- ব্যস্ত জীবনের অনুর্বরতা সম্পর্কে সতর্ক থাকুন।

- আমাদের প্রার্থনা হওয়া উচিত সাধারণের ভালর জন্য। শুধু ঈশ্বরই জানেন কিসে আমাদের ভাল।

- সত্যিকারের জ্ঞান আমাদের সবার কাছেই আসে, যখন আমরা বুঝতে পারি যে আমরা

আমাদের জীবন, আমাদের নিজেদের সম্পর্কে এবং আমাদের চারপাশে যা কিছু আছে তার

সম্পর্কে কত কম জানি।

- সেই সাহসী যে পালিয়ে না গিয়ে তার দায়িত্বে থাকে এবং শত্রুদের বিরুদ্ধে যুদ্ধ করে।

- নিজেকে উন্নয়নের জন্য অন্য মানুষের লেখালেখিতে কাজে লাগাও এই জন্য যে

অন্য মানুষ কিসের জন্য কঠোর পরিশ্রম করে তা তুমি যাতে সহজেই বুঝতে পার।

- সুখ্যাতি অর্জনের উপায় হল তুমি কি হিসেবে আবির্ভূত হতে চাও তার উপক্রম হওয়া।

- তুমি যা হতে চাও তা-ই হও।

- কঠিন যুদ্ধেও সবার প্রতি দয়ালু হও।

- শক্ত মন আলোচনা করে ধারনা নিয়ে, গড়পড়তা মন আলোচনা করে ঘটনা নিয়ে, দুর্বল মন মানুষ নিয়ে আলোচনা করে।

- বন্ধুত্ব কর ধীরে ধীরে, কিন্তু যখন বন্ধুত্ব হবে এটা দৃঢ় কর এবং স্থায়ী কর।

- মৃত্যুই হল মানুষের সর্বাপেক্ষা বড় আশীর্বাদ।

হেমলক: কনিয়াম ম্যাকুলেটাম (হেমলক বা হেমলক বিষ) হল ইউরোপ ও উত্তর আফ্রিকার স্থানীয় গাজর পরিবার এপিয়াসিয়াইয়ের একটি অত্যন্ত বিষাক্ত বহুবর্ষজীবী লতাপাতার সপুষ্পক উদ্ভিদ।[২]

এর রাসায়নিক সংকেত C8H17N. কোনিইন নিউরোটক্সিন জাতীয় বিষ। এটি আক্রান্ত প্রাণীর দেহের স্নায়ুতন্ত্রকে আক্রমণ করে। কোনিইন মূলত প্রাণীদেহের ‘নিউরো-মাসকুলার জাংশন’-কে ব্লক করে দেয়। যে সব তন্তু স্নায়ুর সাথে পেশীর সংযোগ স্থাপন করে সেগুলোকে নিউরো-মাসকুলার জাংশন বলে। নিউরো-মাসকুলার জাংশন ক্ষতিগ্রস্থ হওয়ায় স্নায়ুর সাথে পেশীর সংযোগ বিচ্ছিন্ন হয়ে যায়। ফলে, পেশীকোষ প্যারালাইসিসে আক্রান্ত হয়। শ্বাস-প্রশ্বাসের সাথে যেসব পেশী যুক্ত সেগুলোও প্যারালাইসিসে আক্রান্ত হওয়ায় আক্রান্ত প্রাণীর শ্বাস-প্রশ্বাস বন্ধ হয়ে আসে। হৃদপিন্ড ও মস্তিষ্কে প্রয়োজনীয় পরিমাণ অক্সিজেন সরবরাহ না হওয়ায় আক্রান্ত প্রাণী দ্রুত মৃত্যুর কোলে ঢলে পড়ে।

বিবরণ

হেমলক উদ্ভিদ মানুষসহ অন্য যে কোন প্রাণীর জীবনের জন্য হুমকি। বিশেষ করে তৃণভোজী প্রাণী ও বীজ ভক্ষণকারী পাখিরা হেমলকের বিষে আক্রান্ত হয়ে অনেক সময়ই মারা যায়। হেমলকের ছয় থেকে আটটি পাতায় যে পরিমান বিষ আছে তা কোন মানুষের দেহে প্রবেশ করানো হলে মৃত্যু অনিবার্য! হেমলক বিষে আক্রান্ত হয়ে পৃথিবীর সবচেয়ে আলোচিত মৃত্যুর ঘটনাটি ঘটে খ্রিস্টপূর্ব ৩৯৯ সালে। মহান শিক্ষক ও গ্রিক দার্শনিক সক্রেটিসকে প্রহসনের বিচারে দেয়া হয় মৃত্যুদন্ড! রায়ে বলা হয়, মৃত্যুদন্ড কার্যকর করা হবে হেমলক বিষ পান করিয়ে।

মৃত্যুদন্ড কার্যকর করার দিন, সক্রেটিসের হাতে তুলে দেয়া হয় এক পেয়ালা হেমলক বিষ। সক্রেটিসকে বলা হয়, পেয়ালার বিষ পুরোটুকু পান করতে হবে। এক ফোঁটা বিষও যাতে পেয়ালার বাইরে না পড়ে। সক্রেটিস ধীরস্থিরভাবে এক চুমুকে সবটুকু বিষ পান করেন। এবার সক্রেটিসকে নির্দেশ দেয়া হল, রুমের ভেতরে হাঁটাহাঁটি করার জন্য, যাতে করে বিষ সমস্ত শরীরে ভালোভাবে ছড়িয়ে পড়তে পারে।

সক্রেটিস কিছুক্ষণ পায়চারি করলেন। তার পা দুটি অবশ হয়ে আসতে লাগলো। হৃদযন্ত্রের ক্রিয়া বন্ধ হয়ে আসতে লাগলো। সারা দেহ অবশ হয়ে কিছু সময়ের মাঝেই তিনি মৃত্যুর কোলে ঢলে পড়লেন। মানুষের মাঝে থেকে পতন হল এক উজ্জ্বল নক্ষত্রের!

মহান সক্রেটিসকে যে হেমলক বিষ পান করানো হয়েছিল সেটি ছিল হেমলক গাছের রস। গাছটির বৈজ্ঞানিক নাম Conium maculatum. আইরিশরা এই গাছকে ডাকে Devil’s bread নামে, মানে ‘শয়তানের পাউরুটি’! হেমলক দ্বিবর্ষজীবী গুল্ম জাতীয় উদ্ভিদ। ঝোপ জাতীয় উদ্ভিদ। পাঁচ থেকে আট ফুট লম্বা হয়। ছোট ছোট সাদা রঙ্গের ফুল হয়। ভেজা, স্যাঁতস্যাঁতে জায়গায় জন্মে। নালার কাছে, নদীর ধারে এদেরকে বেশী দেখা যায়। ইউরোপ, পশ্চিম এশিয়া, উত্তর আমেরিকা, উত্তর আফ্রিকা, অস্ট্রেলিয়া, নিউজিল্যান্ড-এ হেমলক বেশি জন্মে। হেমলক গাছ পুরোটাই বিষাক্ত। পাতা, ফুল, ফল, কান্ড, শিকড়- সবটা জুড়েই কোনিইন (Coniine) নামক বিষাক্ত রাসায়নিক উপাদান ছড়িয়ে আছে।

হেমলকের রস পান করে মহান দার্শনিক সক্রেটিসের মৃত্যু পৃথিবীব্যাপী হেমলক বিষকে পরিচিত করে তুলেছে। শেক্সপিয়ার তার কিং লেয়ার, হ্যামলেট ও ম্যাকবেথ নাটকে হেমলক বিষের কথা উল্লেখ করেছেন। সারা পৃথিবীজুড়ে অনেক টিভি সিরিয়াল ও সিনেমার কাহিনীতে হেমলক বিষ ব্যবহার করা হয়েছে। কলকাতার পরিচালক শ্রীজিৎ ব্যানার্জি ২০১২ সালে ‘হেমলক সোসাইটি’ নামে একটি সিনেমা নির্মাণ করেন। ইংরেজ কবি জন কিটস তার ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ কবিতায় হেমলকের কথা উল্লেখ করেছেন

ব্যবহার এবং প্রভাব

সক্রেটিস

প্রাচীন গ্রীসে, হেমলক বিষ দোষী সাব্যস্ত বন্দীদের জন্য ব্যবহৃত হত। হেমলক বিষক্রিয়ায় সবচেয়ে বিখ্যাত শিকার ছিলেন দার্শনিক সক্রেটিস। ৩৯৯ খ্রিস্টপূর্বাব্দে ধর্মদ্রোহিতার জন্য তাকে মৃত্যুদণ্ডাদেশ দেবার পর, সক্রেটিসকে হেমলক গাছের একটি নিষিক্তরস দেওয়া হয়। প্লেটো তার ফিডো রচনায় সক্রেটিসের মৃত্যুর বর্ণনা করেছেন এভাবে:[৩]সক্রেটিসের মৃত্যু, জ্যাক-লুই ডেভিড (১৭৮৭)

The man...laid his hands on him and after a while examined his feet and legs, then pinched his foot hard and asked if he felt it. He said "No"; then after that, his thighs; and passing upwards in this way he showed us that he was growing cold and rigid. And then again he touched him and said that when it reached his heart, he would be gone. The chill had now reached the region about the groin, and uncovering his face, which had been covered, he said – and these were his last words – "Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius. Pay it and do not neglect it." "That," said Crito, "shall be done; but see if you have anything else to say." To this question he made no reply, but after a little while he moved; the attendant uncovered him; his eyes were fixed. And Crito when he saw it, closed his mouth and eyes.[৪]

Socrates (/ˈsɒkrətiːz/;[2] Greek: Σωκράτης [sɔːkrátɛːs], Sōkrátēs; 470/469 – 399 BC)[1] was a classical Greek (Athenian) philosopher credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy. He is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon and the plays of his contemporary Aristophanes. Plato's dialogues are among the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity, though it is unclear the degree to which Socrates himself is "hidden behind his 'best disciple', Plato".[3]

Through his portrayal in Plato's dialogues, Socrates has become renowned for his contribution to the field of ethics, and it is this Platonic Socrates who lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic method, or elenchus. The latter remains a commonly used tool in a wide range of discussions, and is a type of pedagogy in which a series of questions is asked not only to draw individual answers, but also to encourage fundamental insight into the issue at hand. Plato's Socrates also made important and lasting contributions to the field of epistemology, and his ideologies and approach have proven a strong foundation for much Western philosophy that has followed.

Socratic problem

Main article: Socratic problemNothing written by Socrates remains extant. As a result, all first-hand information about him and his philosophies depends upon secondary sources. Furthermore, close comparison between the contents of these sources reveals contradictions, thus creating concerns about the possibility of knowing in-depth the real Socrates. This issue is known as the Socratic problem,[4] or the Socratic question.[5][6]

To understand Socrates and his thought, one must turn primarily to the works of Plato, whose dialogues are thought the most informative source about Socrates' life and philosophy,[7] and also Xenophon.[8] These writings are the Sokratikoi logoi, or Socratic dialogues, which consist of reports of conversations apparently involving Socrates.[9][10]

As for discovering the real-life Socrates, the difficulty is that ancient sources are mostly philosophical or dramatic texts, apart from Xenophon. There are no straightforward histories, contemporary with Socrates, that dealt with his own time and place. A corollary of this is that sources that do mention Socrates do not necessarily claim to be historically accurate, and are often partisan. For instance, those who prosecuted and convicted Socrates have left no testament. Historians therefore face the challenge of reconciling the various evidence from the extant texts in order to attempt an accurate and consistent account of Socrates' life and work. The result of such an effort is not necessarily realistic, even if consistent.

Amid all the disagreement resulting from differences within sources, two factors emerge from all sources pertaining to Socrates. It would seem, therefore, that he was ugly, and that Socrates had a brilliant intellect.[11][12]

Socrates as a figure

The character of Socrates as exhibited in Apology, Crito, Phaedo and Symposium concurs with other sources to an extent to which it seems possible to rely on the Platonic Socrates, as demonstrated in the dialogues, as a representation of the actual Socrates as he lived in history.[13] At the same time, however, many scholars believe that in some works, Plato, being a literary artist, pushed his avowedly brightened-up version of "Socrates" far beyond anything the historical Socrates was likely to have done or said. Also, Xenophon, being an historian, is a more reliable witness to the historical Socrates. It is a matter of much debate over which Socrates it is whom Plato is describing at any given point—the historical figure, or Plato's fictionalization. As British philosopher Martin Cohen has put it, "Plato, the idealist, offers an idol, a master figure, for philosophy. A Saint, a prophet of 'the Sun-God', a teacher condemned for his teachings as a heretic."[14][15]

It is also clear from other writings and historical artefacts, that Socrates was not simply a character, nor an invention, of Plato. The testimony of Xenophon and Aristotle, alongside some of Aristophanes' work (especially The Clouds), is useful in fleshing out a perception of Socrates beyond Plato's work.

Socrates as a philosopher

The problem with discerning Socrates' philosophical views stems from the perception of contradictions in statements made by the Socrates in the different dialogues of Plato. These contradictions produce doubt as to the actual philosophical doctrines of Socrates, within his milieu and as recorded by other individuals.[16] Aristotle, in his Magna Moralia, refers to Socrates in words which make it patent that the doctrine virtue is knowledge was held by Socrates. Within the Metaphysics, he states Socrates was occupied with the search for moral virtues, being the ' first to search for universal definitions for them '.[17]

The problem of understanding Socrates as a philosopher is shown in the following: In Xenophon's Symposium, Socrates is reported as saying he devotes himself only to what he regards as the most important art or occupation, that of discussing philosophy. However, in The Clouds, Aristophanes portrays Socrates as accepting payment for teaching and running a sophist school with Chaerephon. Also, in Plato's Apology and Symposium, as well as in Xenophon's accounts, Socrates explicitly denies accepting payment for teaching. More specifically, in the Apology, Socrates cites his poverty as proof that he is not a teacher.

Two fragments are extant of the writings by Timon of Phlius pertaining to Socrates,[18] although Timon is known to have written to ridicule and lampoon philosophy.[19][20]Socrates Tears Alcibiades from the Embrace of Sensual Pleasure by Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1791)

Biography

Socrates and Alcibiades, by Christoffer Wilhelm EckersbergDetails about the life of Socrates can be derived from three contemporary sources: the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon (both devotees of Socrates), and the plays of Aristophanes. He has been depicted by some scholars, including Eric Havelock and Walter Ong, as a champion of oral modes of communication, standing against the haphazard diffusion of writing.[21]Carnelian gem imprint representing Socrates, Rome, 1st century BC-1st century AD.

In Aristophanes' play The Clouds, Socrates is made into a clown of sorts, particularly inclined toward sophistry, who teaches his students how to bamboozle their way out of debt. However, since most of Aristophanes' works function as parodies, it is presumed that his characterization in this play was also not literal.[22]

Early life

Socrates was born in Alopeke, and belonged to the tribe Antiochis. His father was Sophroniscus, a sculptor, or stonemason.[23][24][25] His mother was a midwife named Phaenarete.[26] Socrates married Xanthippe, who is especially remembered for having an undesirable temperament.[27] She bore for him three sons,[28] Lamprocles, Sophroniscus and Menexenus. Socrates was attracted to teenage boys, as is evident in this encounter with Charmides in a palaestra.[29] However, there is no evidence that he ever had a homosexual or pederastic relationship. His friend Crito of Alopece criticized him for abandoning them when he refused to try to escape before his execution.[30]

Socrates first worked as a stonemason, and there was a tradition in antiquity, not credited by modern scholarship, that Socrates crafted the statues of the Three Graces, which stood near the Acropolis until the 2nd century AD.[31]

Xenophon reports that because youths were not allowed to enter the Agora, they used to gather in workshops surrounding it.[32] Socrates frequented these shops in order to converse with the merchants. Most notable among them was Simon the Shoemaker.[33]

Military service

For a time, Socrates fulfilled the role of hoplite, participating in the Peloponnesian war—a conflict which stretched intermittently over a period spanning 431 to 404 B.C.[34] Several of Plato's dialogues refer to Socrates' military service.

In the monologue of the Apology, Socrates states he was active for Athens in the battles of Amphipolis, Delium, and Potidaea.[35] In the Symposium, Alcibiades describes Socrates' valour in the battles of Potidaea and Delium, recounting how Socrates saved his life in the former battle (219e-221b). Socrates' exceptional service at Delium is also mentioned in the Laches by the General after whom the dialogue is named (181b). In the Apology, Socrates compares his military service to his courtroom troubles, and says anyone on the jury who thinks he ought to retreat from philosophy must also think soldiers should retreat when it seems likely that they will be killed in battle.[36]

Epistates at the trial of the six commanders

Main article: Trial of the generalsDuring 406, he participated as a member of the Boule.[37] His tribe the Antiochis held the Prytany on the day it was debated what fate should befall the generals of the Battle of Arginusae, who abandoned the slain and the survivors of foundered ships to pursue the defeated Spartan navy.[24][38][39]

According to Xenophon, Socrates was the Epistates for the debate,[40] but Delebecque and Hatzfeld think this is an embellishment, because Xenophon composed the information after Socrates' death [41]

The generals were seen by some to have failed to uphold the most basic of duties, and the people decided upon capital punishment. However, when the prytany responded by refusing to vote on the issue, the people reacted with threats of death directed at the prytany itself. They relented, at which point Socrates alone as epistates blocked the vote, which had been proposed by Callixeinus.[42][43] The reason he gave was that "in no case would he act except in accordance with the law".[44]

The outcome of the trial was ultimately judged to be a miscarriage of justice, or illegal, but, actually, Socrates' decision had no support from written statutory law, instead being reliant on favouring a continuation of less strict and less formal nomos law.[43][45][46]

Arrest of Leon

Plato's Apology, parts 32c to 32d, describes how Socrates and four others were summoned to the Tholos, and told by representatives of the oligarchy of the Thirty (the oligarchy began ruling in 404 B.C.) to go to Salamis, and from there, to return to them with Leon the Salaminian. He was to be brought back to be subsequently executed. However, Socrates returned home and did not go to Salamis as he was expected to.[47][48]

Trial and death

Main article: Trial of SocratesSocrates lived during the time of the transition from the height of the Athenian hegemony to its decline with the defeat by Sparta and its allies in the Peloponnesian War. At a time when Athens sought to stabilize and recover from its humiliating defeat, the Athenian public may have been entertaining doubts about democracy as an efficient form of government. Socrates appears to have been a critic of democracy,[49] and some scholars interpret his trial as an expression of political infighting.[50]

Claiming loyalty to his city, Socrates clashed with the current course of Athenian politics and society.[51] He praises Sparta, archrival to Athens, directly and indirectly in various dialogues. One of Socrates' purported offenses to the city was his position as a social and moral critic. Rather than upholding a status quo and accepting the development of what he perceived as immorality within his region, Socrates questioned the collective notion of "might makes right" that he felt was common in Greece during this period. Plato refers to Socrates as the "gadfly" of the state (as the gadfly stings the horse into action, so Socrates stung various Athenians), insofar as he irritated some people with considerations of justice and the pursuit of goodness.[52] His attempts to improve the Athenians' sense of justice may have been the cause of his execution.The Death of Socrates, by Jacques-Louis David (1787)

According to Plato's Apology, Socrates' life as the "gadfly" of Athens began when his friend Chaerephon asked the oracle at Delphi if anyone were wiser than Socrates; the Oracle responded that no-one was wiser. Socrates believed the Oracle's response was not correct, because he believed he possessed no wisdom whatsoever. He proceeded to test the riddle by approaching men considered wise by the people of Athens—statesmen, poets, and artisans—in order to refute the Oracle's pronouncement. Questioning them, however, Socrates concluded: while each man thought he knew a great deal and was wise, in fact they knew very little and were not wise at all. Socrates realized the Oracle was correct; while so-called wise men thought themselves wise and yet were not, he himself knew he was not wise at all, which, paradoxically, made him the wiser one since he was the only person aware of his own ignorance. Socrates' paradoxical wisdom made the prominent Athenians he publicly questioned look foolish, turning them against him and leading to accusations of wrongdoing. Socrates defended his role as a gadfly until the end: at his trial, when Socrates was asked to propose his own punishment, he suggested a wage paid by the government and free dinners for the rest of his life instead, to finance the time he spent as Athens' benefactor.[53] He was, nevertheless, found guilty of both corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens and of impiety ("not believing in the gods of the state"),[54] and subsequently sentenced to death by drinking a mixture containing poison hemlock.[55][56][57][58]

Xenophon and Plato agree that Socrates had an opportunity to escape, as his followers were able to bribe the prison guards. There have been several suggestions offered as reasons why he chose to stay:Bust of Socrates in the Vatican Museum

- He believed such a flight would indicate a fear of death, which he believed no true philosopher has.

- If he fled Athens his teaching would fare no better in another country, as he would continue questioning all he met and undoubtedly incur their displeasure.

- Having knowingly agreed to live under the city's laws, he implicitly subjected himself to the possibility of being accused of crimes by its citizens and judged guilty by its jury. To do otherwise would have caused him to break his "social contract" with the state, and so harm the state, an unprincipled act.

- If he escaped at the instigation of his friends, then his friends would become liable in law.[59]

Socrates' death is described at the end of Plato's Phaedo. Socrates turned down Crito's pleas to attempt an escape from prison. After drinking the poison, he was instructed to walk around until his legs felt numb. After he lay down, the man who administered the poison pinched his foot; Socrates could no longer feel his legs. The numbness slowly crept up his body until it reached his heart. Shortly before his death, Socrates speaks his last words to Crito: "Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don't forget to pay the debt."

Asclepius was the Greek god for curing illness, and it is likely Socrates' last words meant that death is the cure—and freedom, of the soul from the body. Additionally, in Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths, Robin Waterfield adds another interpretation of Socrates' last words. He suggests that Socrates was a voluntary scapegoat; his death was the purifying remedy for Athens' misfortunes. In this view, the token of appreciation for Asclepius would represent a cure for Athens' ailments.[52]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Plato |

|---|

Plato from Raphael's The School of Athens (1509–1511)

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

Socratic method

Main article: Socratic method

Perhaps his most important contribution to Western thought is his dialectic

method of inquiry, known as the Socratic method or method of

"elenchus", which he largely applied to the examination of key moral

concepts such as the Good and Justice. It was first described by Plato in the Socratic Dialogues.

To solve a problem, it would be broken down into a series of questions,

the answers to which gradually distill the answer a person would seek.

The influence of this approach is most strongly felt today in the use of

the scientific method, in which hypothesis

is the first stage. The development and practice of this method is one

of Socrates' most enduring contributions, and is a key factor in earning

his mantle as the father of political philosophy, ethics or moral philosophy, and as a figurehead of all the central themes in Western philosophy.To illustrate the use of the Socratic method, a series of questions are posed to help a person or group to determine their underlying beliefs and the extent of their knowledge. The Socratic method is a negative method of hypothesis elimination, in that better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. It was designed to force one to examine one's own beliefs and the validity of such beliefs.

An alternative interpretation of the dialectic is that it is a method for direct perception of the Form of the Good. Philosopher Karl Popper describes the dialectic as "the art of intellectual intuition, of visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances."[61] In a similar vein, French philosopher Pierre Hadot suggests that the dialogues are a type of spiritual exercise. Hadot writes that "in Plato's view, every dialectical exercise, precisely because it is an exercise of pure thought, subject to the demands of the Logos, turns the soul away from the sensible world, and allows it to convert itself towards the Good."[62]

Philosophical beliefs

The beliefs of Socrates, as distinct from those of Plato, are difficult to discern. Little in the way of concrete evidence exists to demarcate the two. The lengthy presentation of ideas given in most of the dialogues may be the ideas of Socrates himself, but which have been subsequently deformed or changed by Plato, and some scholars think Plato so adapted the Socratic style as to make the literary character and the philosopher himself impossible to distinguish. Others argue that he did have his own theories and beliefs.[63] There is a degree of controversy inherent in the identifying of what these might have been, owing to the difficulty of separating Socrates from Plato and the difficulty of interpreting even the dramatic writings concerning Socrates. Consequently, distinguishing the philosophical beliefs of Socrates from those of Plato and Xenophon has not proven easy, so it must be remembered that what is attributed to Socrates might actually be more the specific concerns of these two thinkers instead.The matter is complicated because the historical Socrates seems to have been notorious for asking questions but not answering, claiming to lack wisdom concerning the subjects about which he questioned others.[64]

If anything in general can be said about the philosophical beliefs of Socrates, it is that he was morally, intellectually, and politically at odds with many of his fellow Athenians. When he is on trial for heresy and corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, he uses his method of elenchos to demonstrate to the jurors that their moral values are wrong-headed. He tells them they are concerned with their families, careers, and political responsibilities when they ought to be worried about the "welfare of their souls". Socrates' assertion that the gods had singled him out as a divine emissary seemed to provoke irritation, if not outright ridicule. Socrates also questioned the Sophistic doctrine that arete (virtue) can be taught. He liked to observe that successful fathers (such as the prominent military general Pericles) did not produce sons of their own quality. Socrates argued that moral excellence was more a matter of divine bequest than parental nurture. This belief may have contributed to his lack of anxiety about the future of his own sons.

Also, according to A. A. Long, "There should be no doubt that, despite his claim to know only that he knew nothing, Socrates had strong beliefs about the divine", and, citing Xenophon's Memorabilia, 1.4, 4.3,:

According to Xenophon, he was a teleologist who held that god arranges everything for the best.[65]Socrates frequently says his ideas are not his own, but his teachers'. He mentions several influences: Prodicus the rhetor and Anaxagoras the philosopher. Perhaps surprisingly, Socrates claims to have been deeply influenced by two women besides his mother: he says that Diotima (c.f. Plato's Symposium), a witch and priestess from Mantinea, taught him all he knows about eros, or love; and that Aspasia, the mistress of Pericles, taught him the art of rhetoric.[66] John Burnet argued that his principal teacher was the Anaxagorean Archelaus but his ideas were as Plato described them; Eric A. Havelock, on the other hand, considered Socrates' association with the Anaxagoreans to be evidence of Plato's philosophical separation from Socrates.

Socratic paradoxes

Many of the beliefs traditionally attributed to the historical Socrates have been characterized as "paradoxical" because they seem to conflict with common sense. The following are among the so-called Socratic paradoxes:[67]- No one desires evil.

- No one errs or does wrong willingly or knowingly.

- Virtue—all virtue—is knowledge.

- Virtue is sufficient for happiness.

Knowledge

The statement "I know that I know nothing" is often attributed to Socrates, based on a statement in Plato's Apology.[69] The conventional interpretation of this is that Socrates' wisdom was limited to an awareness of his own ignorance. Socrates considered virtuousness to require or consist of phronēsis, "thought, sense, judgement, practical wisdom, [and] prudence."[70][71] Therefore, he believed that wrongdoing and behaviour that was not virtuous resulted from ignorance, and that those who did wrong knew no better.[72]The one thing Socrates claimed to have knowledge of was "the art of love" (ta erôtikê). This assertion seems to be associated with the word erôtan, which means to ask questions. Therefore, Socrates is claiming to know about the art of love, insofar as he knows how to ask questions.[73][74]

The only time he actually claimed to be wise was within Apology, in which he says he is wise "in the limited sense of having human wisdom".[75] It is debatable whether Socrates believed humans (as opposed to gods like Apollo) could actually become wise. On the one hand, he drew a clear line between human ignorance and ideal knowledge; on the other, Plato's Symposium (Diotima's Speech) and Republic (Allegory of the Cave) describe a method for ascending to wisdom.

In Plato's Theaetetus (150a), Socrates compares his treatment of the young people who come to him for philosophical advice to the way midwives treat their patients, and the way matrimonial matchmakers act. He says that he himself is a true matchmaker (προμνηστικός promnestikós) in that he matches the young man to the best philosopher for his particular mind. However, he carefully distinguishes himself from a panderer (προᾰγωγός proagogos) or procurer. This distinction is echoed in Xenophon's Symposium (3.20), when Socrates jokes about his certainty of being able to make a fortune, if he chose to practice the art of pandering. For his part as a philosophical interlocutor, he leads his respondent to a clearer conception of wisdom, although he claims he is not himself a teacher (Apology). His role, he claims, is more properly to be understood as analogous to a midwife (μαῖα maia).[76][77]

In the Theaetetus, Socrates explains that he is himself barren of theories, but knows how to bring the theories of others to birth and determine whether they are worthy or mere "wind eggs" (ἀνεμιαῖον anemiaion). Perhaps significantly, he points out that midwives are barren due to age, and women who have never given birth are unable to become midwives; they would have no experience or knowledge of birth and would be unable to separate the worthy infants from those that should be left on the hillside to be exposed. To judge this, the midwife must have experience and knowledge of what she is judging.[78][79]

Virtue

Bust of Socrates in the Palermo Archaeological Museum.

The idea that there are certain virtues formed a common thread in Socrates' teachings. These virtues represented the most important qualities for a person to have, foremost of which were the philosophical or intellectual virtues. Socrates stressed that "the unexamined life is not worth living [and] ethical virtue is the only thing that matters."[82]

Politics

It is argued that Socrates believed "ideals belong in a world only the wise man can understand",[83] making the philosopher the only type of person suitable to govern others. In Plato's dialogue the Republic, Socrates openly objected to the democracy that ran Athens during his adult life. It was not only Athenian democracy: Socrates found short of ideal any government that did not conform to his presentation of a perfect regime led by philosophers, and Athenian government was far from that. It is, however, possible that the Socrates of Plato's Republic is colored by Plato's own views. During the last years of Socrates' life, Athens was in continual flux due to political upheaval. Democracy was at last overthrown by a junta known as the Thirty Tyrants, led by Plato's relative, Critias, who had once been a student and friend of Socrates. The Tyrants ruled for about a year before the Athenian democracy was reinstated, at which point it declared an amnesty for all recent events.Socrates' opposition to democracy is often denied, and the question is one of the biggest philosophical debates when trying to determine exactly what Socrates believed. The strongest argument of those who claim Socrates did not actually believe in the idea of philosopher kings is that the view is expressed no earlier than Plato's Republic, which is widely considered one of Plato's "Middle" dialogues and not representative of the historical Socrates' views. Furthermore, according to Plato's Apology of Socrates, an "early" dialogue, Socrates refused to pursue conventional politics; he often stated he could not look into other's matters or tell people how to live their lives when he did not yet understand how to live his own. He believed he was a philosopher engaged in the pursuit of Truth, and did not claim to know it fully. Socrates' acceptance of his death sentence after his conviction can also be seen to support this view. It is often claimed much of the anti-democratic leanings are from Plato, who was never able to overcome his disgust at what was done to his teacher. In any case, it is clear Socrates thought the rule of the Thirty Tyrants was also objectionable; when called before them to assist in the arrest of a fellow Athenian, Socrates refused and narrowly escaped death before the Tyrants were overthrown. He did, however, fulfill his duty to serve as Prytanis when a trial of a group of Generals who presided over a disastrous naval campaign were judged; even then, he maintained an uncompromising attitude, being one of those who refused to proceed in a manner not supported by the laws, despite intense pressure.[84] Judging by his actions, he considered the rule of the Thirty Tyrants less legitimate than the Democratic Senate that sentenced him to death.

Socrates' apparent respect for democracy is one of the themes emphasized in the 2008 play Socrates on Trial by Andrew David Irvine. Irvine argues that it was because of his loyalty to Athenian democracy that Socrates was willing to accept the verdict of his fellow citizens. As Irvine puts it, "During a time of war and great social and intellectual upheaval, Socrates felt compelled to express his views openly, regardless of the consequences. As a result, he is remembered today, not only for his sharp wit and high ethical standards, but also for his loyalty to the view that in a democracy the best way for a man to serve himself, his friends, and his city—even during times of war—is by being loyal to, and by speaking publicly about, the truth."[85]

Hemlock: Conium maculatum (hemlock or poison hemlock) is a highly poisonous perennial herbaceous flowering plant in the carrot family Apiaceae, native to Europe and North Africa.[2]

Description

It is a herbaceous biennial plant that grows to 1.5–2.5 m (5–8 ft) tall, with a smooth, green, hollow stem, usually spotted or streaked with red or purple on the lower half of the stem. All parts of the plant are hairless (glabrous). The leaves are two- to four-pinnate, finely divided and lacy, overall triangular in shape, up to 50 cm (20 in) long and 40 cm (16 in) broad. The flowers are small, white, clustered in umbels up to 10–15 cm (4–6 in) across. When crushed, the leaves and root emit a rank, unpleasant odor often compared to that of parsnips. It produces a large number of seeds that allow the plant to form thick stands in modified soils.Name

Conium maculatum is known by several common names. In addition to the English poison hemlock, the Australian Carrot Fern,[3] and the Irish devil's bread or devil's porridge, poison parsley, spotted corobane, and spotted hemlock are used. The plant should not be confused with the coniferous tree Tsuga, also known by the common name hemlock even though the two plants are quite different. The dried stems are sometimes called kecksies or kex.[4][5]Conium comes from the Greek konas (meaning to whirl), in reference to vertigo, one of the symptoms of ingesting the plant.[6]

Distribution

Conium maculatum is native in temperate regions of Europe, West Asia, and North Africa. It has been introduced and naturalised in many other areas, including Asia, North America, Australia, and New Zealand.[7][8][3] It is often found on poorly drained soils, particularly near streams, ditches, and other surface water. It also appears on roadsides, edges of cultivated fields, and waste areas.[7] It is considered an invasive species in 12 U.S. states.[9]Ecology

Conium maculatum grows in damp areas,[10] but also on drier rough grassland, roadsides, and disturbed ground. It is used as a food plant by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, including silver-ground carpet. Poison hemlock flourishes in the spring, when most other forage is gone. All plant parts are poisonous, but once the plant is dried, the poison is greatly reduced, although not gone completely.[citation needed]Biochemistry

Chemical structure of coniine

Poison

A 19th-century illustration of C. maculatum

Hemlock seed heads in late summer

Coniine has a chemical structure and pharmacological properties similar to nicotine,[7][13] and disrupts the workings of the central nervous system through action on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. In high enough concentrations, coniine can be dangerous to humans and livestock.[12] Due to high potency, the ingestion of seemingly small doses can easily result in respiratory collapse and death.[14] Coniine causes death by blocking the neuromuscular junction in a manner similar to curare; this results in an ascending muscular paralysis with eventual paralysis of the respiratory muscles which results in death due to lack of oxygen to the heart and brain. Death can be prevented by artificial ventilation until the effects have worn off 48–72 hours later.[7] For an adult, the ingestion of more than 100 mg (0.1 gram) of coniine (about six to eight fresh leaves, or a smaller dose of the seeds or root) may be fatal.[15]

Isolation of the alkaloids

Of the total alkaloids of hemlock isolated by the method of Chemnitius[16] and fractionally distilled, the portion boiling up to 190 °C (374 °F) contains most of the coniine, gamma-coniceine and N-methylconiine, while conhydrine and pseudoconhydrine remain in the higher boiling residues. For the separation of coniine from coniceine, Wolffenstein[17][18] recommends conversion into hydrochlorides. These are dried and extracted with acetone, which dissolves coniceine hydrochloride, leaving the coniine salt, from which the base may then be regenerated. For final purification, the coniine is converted into the D-hydrogen tartrate. It is sometimes necessary to start crystallisation by adding a crystal of the desired salt. Von Braun[19][20] distills the crude mixed alkaloids until the temperature rises to 190 °C (374 °F), benzoylates the distillate, extracts the tertiary bases by shaking an ethereal solution with dilute acid, pours the concentrated ethereal solution into light petroleum to precipitate most of the benzoyl-δ-aminobutyl propyl ketone formed by the action of benzoyl chloride on coniceine, distills the solvent from the filtrate and collects from the residue the fraction boiling at 200–210 °C (392–410 °F)/16 mmHg (2.1 kPa), which is nearly pure benzoylconiine (bp. 203–204 °C (397–399 °F)/16 mmHg). From this a mixture of D- and L-coniines are obtained by hydrolysis, the former predominating.Uses and effects

Socrates

The Death of Socrates, by Jacques-Louis David (1787)

Main article: Trial of Socrates

In ancient Greece, hemlock was used to poison condemned prisoners.

The most famous victim of hemlock poisoning is the philosopher Socrates. After being condemned to death for impiety and corrupting the young men of Athens, in 399 BC, Socrates was given a potent infusion of the hemlock plant. Plato described Socrates' death in the Phaedo:[21]The man...laid his hands on him and after a while examined his feet and legs, then pinched his foot hard and asked if he felt it. He said "No"; then after that, his thighs; and passing upwards in this way he showed us that he was growing cold and rigid. And then again he touched him and said that when it reached his heart, he would be gone. The chill had now reached the region about the groin, and uncovering his face, which had been covered, he said – and these were his last words – "Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius. Pay it and do not neglect it." "That," said Crito, "shall be done; but see if you have anything else to say." To this question he made no reply, but after a little while he moved; the attendant uncovered him; his eyes were fixed. And Crito when he saw it, closed his mouth and eyes.[22]Although many have questioned whether this is a factual account, careful attention to Plato's words, modern and ancient medicine, and other ancient Greek sources point to the above account being consistent with Conium poisoning.[23]

Effects on animals

Conium maculatum is poisonous to animals. In a short time, the alkaloids produce a potentially fatal neuromuscular blockage when the respiratory muscles are affected. Acute toxicity, if not lethal, may resolve in the spontaneous recovery of the affected animals provided further exposure is avoided.It has been observed that poisoned animals tend to return to feed on this plant. Chronic toxicity affects only pregnant animals. When they are poisoned by C. maculatum during the fetus' organ formation period, the offspring is born with malformations, mainly palatoschisis and multiple congenital contractures (MCC; frequently described as arthrogryposis). Chronic toxicity is irreversible and although MCC can be surgically corrected in some cases, most of the malformed animals are lost. Such losses may be underestimated, at least in some regions, because of the difficulty in associating malformations with the much earlier maternal poisoning.

Since no specific antidote is available, prevention is the only way to deal with the production losses caused by the plant. Control with herbicides and grazing with less susceptible animals (such as sheep) have been suggested. C. maculatum alkaloids can enter the human food chain via milk and fowl.[24]

No comments:

Post a Comment